SEVEN YEAR ITCH

Seven years is the longest I ever did anything. Tomorrow will be the seventh anniversary of my first day at Dark Horse Comics. I started at the age of twenty-four, and since then I have changed so much, as have my friends in and out of comics, the company, the comics field, and Portland, where I live. My title has changed three times, from Editorial Assistant to Assistant Editor, then to Associate Editor, and finally to Editor. The only thing that didn’t change was that I worked at Dark Horse.

Yesterday was my last day. Given all that has changed in my life and in comics, I’m excited for thirty-one-year-old me to strike a different path from twenty-four-year-old me and am thrilled to announce the beginning of my career as a freelance editor. My initial client list is made up of projects I am honored to be a part of, and I’m available to take on more, so keep reading.

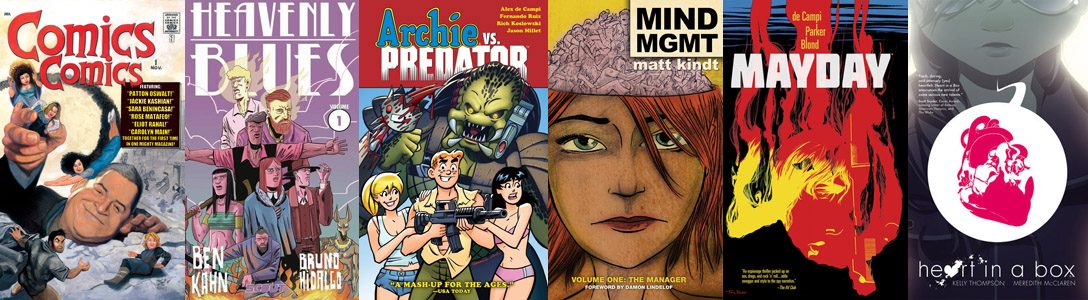

I noticed several months ago that, by a quirk of the publishing schedule, the two series I have edited the longest and with which I am most associated, MIND MGMT and Grindhouse, would end at the same time, with my most nutso project, Archie vs. Predator, concluding shortly before. As it happened, the final issues of MIND MGMT and Grindhouse were both released last Wednesday. At the same time, some intriguing freelance opportunities presented themselves, and I decided to take the plunge.

I’m leaving Dark Horse on good terms and intend to keep up my relationship with the company. I love many people who still work there, and I look forward to continuing to see them outside of work and to reading the comics they’re working on. I’m sad for all the projects I won’t see to the end, but I’m proud of each of them and confident in and thankful to the editors taking over for me.

SEVEN YEARS GOOD LUCK

It’s difficult for me to imagine the opportunities Dark Horse provided a kid just starting out in his career happening anywhere else. The very first thing I worked on was an issue of Stan Sakai’s Usagi Yojimbo, a favorite since my first year of high school. Within a month or two I was on the phone with Dave Gibbons, discussing the mammoth Life and Times of Martha Washington. Both happened because I was working for legendary editor Diana Schutz, and assisting her it sometimes felt like I got to work with just about everyone in comics. Assisting Diana is how I first came to work with Matt Kindt, Alex de Campi, and Jeff Lemire, three of the talents who, along with Stan, really defined my last years at Dark Horse (Jeff and Dean Ormston’s Black Hammer has been delayed until next year, and missing its debut is one of my biggest regrets about leaving, but I am immensely proud of the work we did and know it’s in good hands).

Once I undertook my own projects, not everyone at Dark Horse always understood what I was trying to do, but that didn’t stop them from letting me make moves like bringing Jeff Parker and Erica Moen’s webcomic Bucko to Dark Horse, opening the door to Monkeybrain with Paul Tobin and Colleen Coover’s Bandette, abetting Alex de Campi as she transcended every boundary of good taste in Grindhouse, developing a model for digitally serializing original graphic novels in advance of their order periods, creating the template for our Gallery Edition books and adding complicating features like massive foldouts, updating Creepy and Eerie for a modern audience, or giving weird newcomers Damon Gentry and Aaron Conley their first shot with Sabertooth Swordsman, which went on to win the Russ Manning Award for Promising Newcomer. They also put beloved franchises like Archie, Predator (and therefore Archie vs. Predator) and The Terminator in my hands, as well as acclaimed game studios like Naughty Dog, with comics based on The Last of Us and coffee table books of Uncharted and the art of the studio. I even have my name in a few Star Wars comics for some reason.

And, fatefully, I was assigned MIND MGMT #1, back when no one knew whether it would make it as an ongoing or end up a six-issue miniseries. Last week saw Matt Kindt finish the series on his own terms, after thirty-seven issues and a little over three years. I don’t know what my life or career would look like right now if not for receiving that assignment, and for that alone I would have always been grateful for my years at Dark Horse, but I am fortunate to have so many other reasons.

SEVEN YEAR PLAN

The future is a little terrifying, but I’m also the most excited I’ve been in years. I don’t know how long I’ll stick around Portland, but it will remain my home base for the time being, with more frequent visits to Los Angeles mixed in. One thing I don’t plan to change is my being a part of comics. I am as enchanted today as I was when I started by the possibilities of words and pictures and believe to my core in comics’ central role in innovating visual storytelling today. I hope to stay in comics as long as I am working, even if my role in it is evolving.

It’s probably more accurate to say my role is expanding, and I’m very pleased that the immediate future includes a continuation of my old one. Dark Horse will be among my first new clients, as I’ll be finishing a handful of projects on a freelance basis. I’ll also be starting immediately on some new Image series I’m excited about and lending a hand to a few existing ones that I read devotedly, and I’m currently in talks with a couple of nontraditional publishers about their upcoming comics lines. After years of doing things one way, I look forward to doing things five or six ways at once.

And that’s just the stuff I know about. Equally compelling are the projects that I don’t know are out there, the other Image series in search of an editor, the self-published books by authors who want a sounding board, the brilliant pitches in need of a helping hand to shape them, the graphic novel that’s complete except for a final proofread. I’m throwing the net wide, and I look forward to consulting/editing/proofreading on all kinds of projects.

If you’re looking, please send inquiries about experience, services, and rates to editing@brendanhwright.com. I’ll also be roaming Rose City Comic Con and New York Comic Con. And if you’re interested in seeing how this whole being-my-own-boss thing goes, follow me on Twitter at @BrendanWasright. Let’s keep comics the most vital entertainment medium going—together.